-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

High-Low Agreements Can Prevent Large Plaintiff Verdicts

Publication

Medical Marijuana and Workers’ Compensation

Publication

Secondary Peril Events are Becoming Primary en

Publication

Risks of Underinsurance in Property and Possible Regulation

Publication

Benefits of Generative Search: Unlocking Real-Time Knowledge Access

Publication

Battered Umbrella – A Market in Urgent Need of Fixing -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Thinking Differently About Genetics and Insurance

Publication

Post-Acute Care: The Need for Integration

Publication

Trend Spotting on the Accelerated Underwriting Journey

Publication

Medicare Supplement Premium Rates – Looking to the Past and Planning for the Future U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Future Impacts on Mortality [Video] -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

Obesity – Treatments, Risks, and Research for Claims Professionals to Know

July 10, 2023

Patricia Bailer

English

Despite increased awareness of the problem, the obesity epidemic continues in the U.S. while obesity rates are increasing around the world. A few years back, I authored an article on this topic. In revisiting the research, I’m amazed how much has changed on the obesity front. My colleague, Bharath UP, recently addressed obesity from a mortality perspective in Asia, so I’ll not reiterate much of his good work. Rather I’ll address obesity from a morbidity perspective.

What is obesity?

The World Health Organization declared the obesity epidemic a public health crisis1 with obese individuals at higher risk of numerous diseases including cancer, heart disease, stroke, and joint disease to mention a few. Overweight and obesity are defined based on body mass index (BMI) which is determined as weight (in kg) divided by height (in m) squared. Waist circumference can be used in combination with a BMI value to evaluate health risk for individuals.2 Healthy weight is associated with a BMI between 18‑24.9; overweight with a BMI between 25 and 29.9, and obese if 30 and greater.

The reliance on BMI as an indicator of obesity is being challenged in some countries,3 and use of lower BMI thresholds are often relied upon in various markets.

Clinical Guidelines: Classification of Overweight and Obesity

Disease Risk* Relative to Normal Weight and Waist Circumference |

||||

|

BMI (kg/m²) |

Obesity Class |

Men ≤102 cm (≤40 in) |

Men >102 cm (>40 in) |

Underweight |

<18.5 |

|

— |

— |

Normal** |

18.5–24.9 |

|

— |

— |

Overweight |

25.0–29.9 |

|

Increased |

High |

Obesity |

30.0–34.9 |

I |

High |

Very High |

|

35.0–39.9 |

II |

Very High |

Very High |

Extreme Obesity |

≥40 |

III |

Extremely High |

Extremely High |

* Disease risk for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and CVD |

||||

Why does obesity remain an important topic?

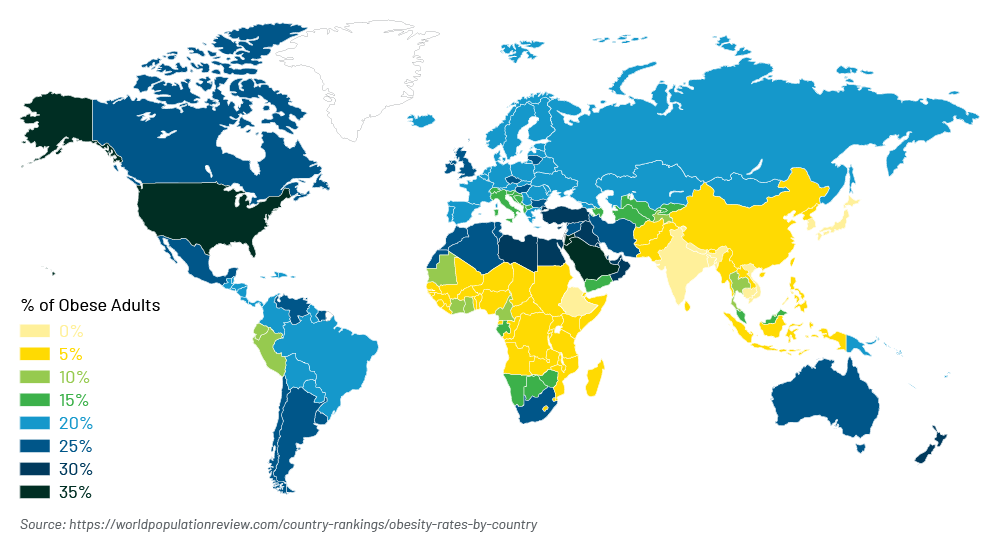

Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975 with more than 1.9 billion adults overweight and more than 650 million of them obese4 (that’s 39% of adults overweight and 13% obese). Some countries such as the United Kingdom have introduced government programs and strategies as means to tackle obesity.

Comorbidity issues and downstream implications to one’s morbidity (see prior Gen Re articles) and mortality cannot be overlooked.

The four major impacts of obesity on morbidity include cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke), Type 2 diabetes mellitus, musculoskeletal disorders like osteoarthritis, and some cancers (endometrial, breast and colon). As my colleague Bharath points out in his article, these conditions may cause premature death and/or substantial impairments.

Is obesity reversible?

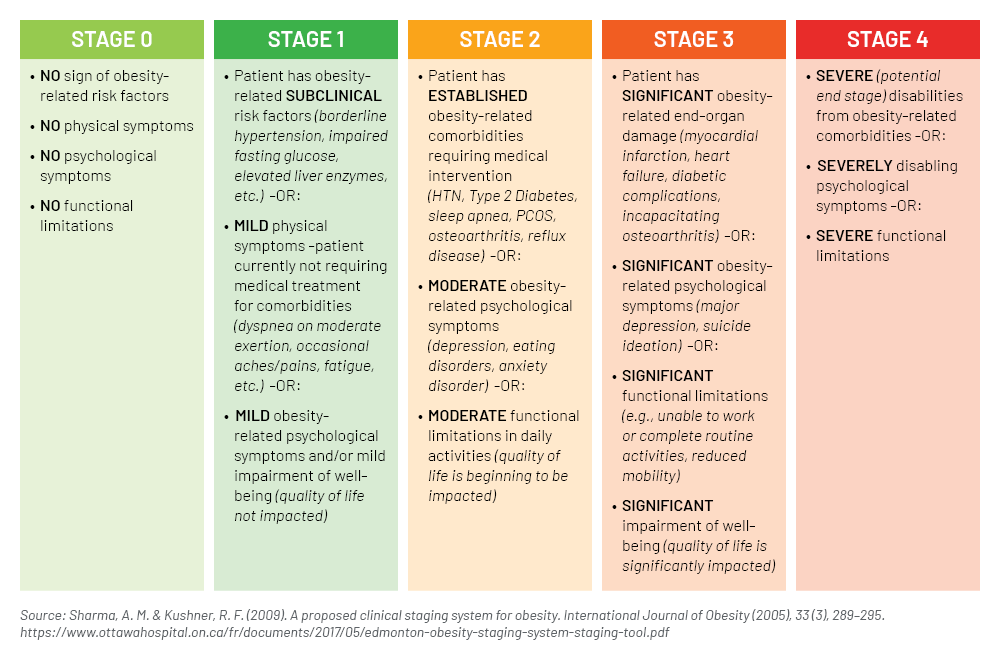

The million-dollar question is whether obesity is reversible. The answer is yes and, depending on how much permanent damage is done to key organs like the heart, may improve mortality if reversed. (See Obesity Staging Chart below.) The cards unfortunately are stacked against those obese since many do not stick with a set course of treatment. Researchers say <1% of people with obesity get back to a healthy body weight and maintain it.5

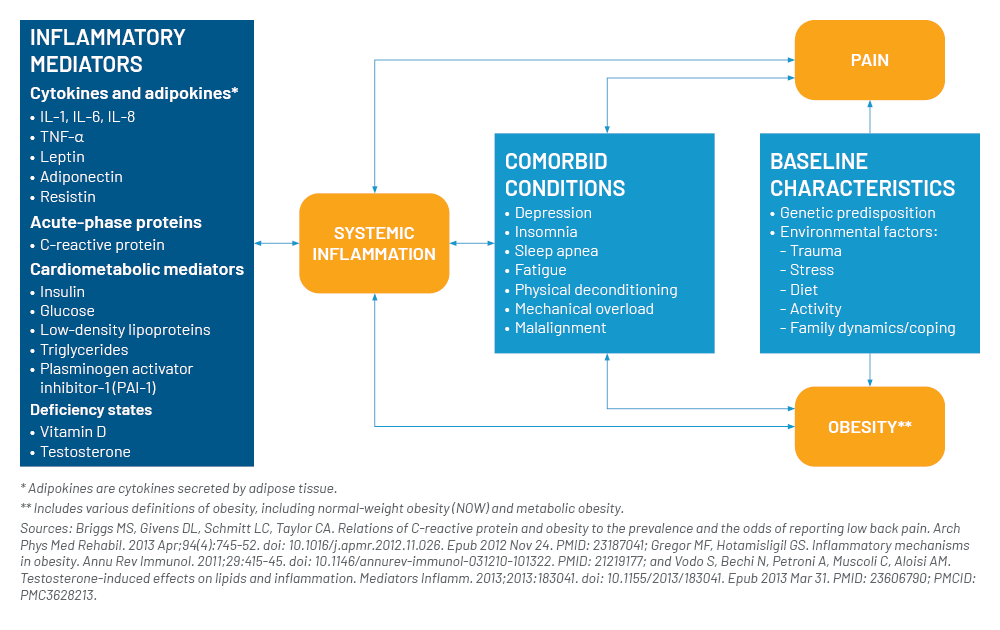

However, the research excluded patients who underwent bariatric bypass surgery that has been shown to help patients with severe obesity. We do know it’s more difficult to lose weight than to gain it especially given the symptoms resulting from obesity, making exercise and lifestyle changes feel insurmountable especially when systemic inflammation and corresponding pain is involved.

Other challenges such as metabolic disease, joint and skeletal problems, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, also make it seem like implementing a modest weight loss program or fitness intervention is overwhelming. Thus, tailoring interests, needs and abilities of individuals to reduce attrition in targeted intervention programs may help.

Studies

The Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) is a five-stage system of obesity classification that considers parameters in order to determine the optimal obesity treatment.6 Using the EOSS tool may enhance clinical obesity information over using BMI alone.7

EOSS: Edmonton Obesity Staging System – Staging Tool

Some studies suggest obesity impacts brain volume and executive level functioning in cognition, which may or may not lead to a higher risk of dementia (including vascular dementia) and Alzheimer’s. Obesity may lead to several metabolic changes such as hypertension which may accelerate arterial aging and thus may impair cognitive function such as attention, executive function, and decision making. More research needs to be done here, and this article is not to say people with high BMIs have cognitive deficits because they don’t. In fact, treatment of obesity may improve cognitive function. In randomized, double-blind studies,8 elderly patients with MCI and obesity showed improved verbal memory, verbal fluency, executive function, and global cognition after a calorie restricted diet alone.

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, many countries reported those quarantined were more likely to show signs of depression, panic, and anxiety symptomatology. Further, many also reported average weight gain in individuals to be between 25‑30 pounds.

Treatment Advances

Research and medical advancement on the obesity front is accelerating faster than ever before. Claims professionals should understand the complexity obesity presents, treatment advances, and corresponding challenges.

Some treatment regimens require surgical interventions like the lap band (e.g., putting a rubber band around your stomach to shrink its intake) and gastric bypass/gastric sleeve (e.g., where part of the stomach is cut, and intestines rerouted), and are not in and of themselves permanent solutions to the causation of obesity. If the underlying cause is not treated, the surgical intervention may only offer temporary relief.

While weight loss medications don’t come without potential side effects, the risk and potential complications associated with more interventional options such as bariatric surgery are significant. If treatment with injectables like Mounjaro (not yet widely approved or endorsed) and Semaglutide continue to offer similar results in non-invasive approaches, demand for weight loss surgery may significantly decrease. This is important for claims resources to understand. When assessing one’s occupation in a case, there’s need to understand what’s driving the loss of income (e.g., due to an impairment or extenuating circumstance such as demand for service drying up).

Since the world of bariatric treatment is ever-changing, it’s important for claims professionals to understand the advancements. For example, gene research is suggestive that even applying all appropriate treatment measures, one can still be obese. If one can achieve an overall 10% weight reduction, it can have immediate positive impacts on one’s ability to function, and more significantly engage in less invasive lifestyle changes to improve overall health and even reduce A1C levels, to mention a few.

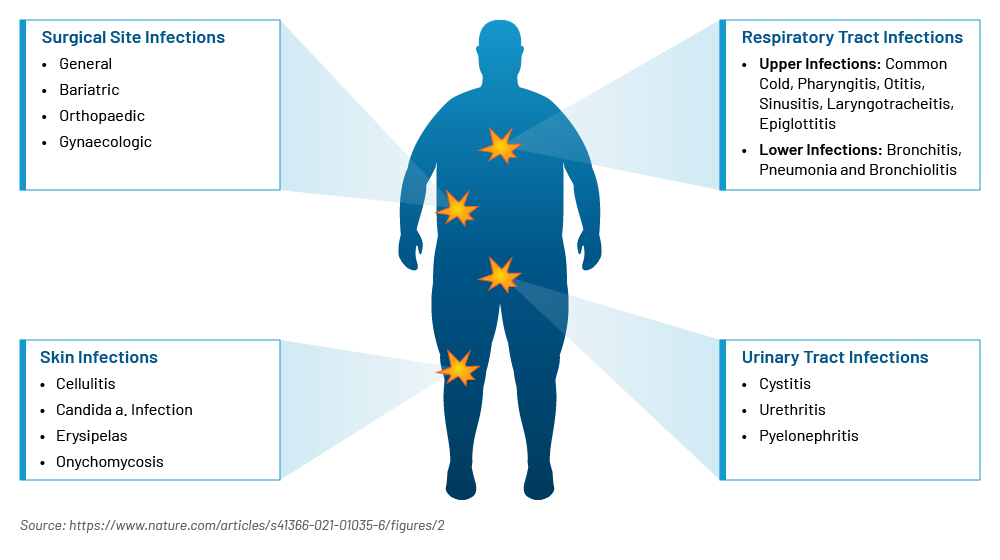

Some of the drawbacks are the speed in which the weight loss occurs and the consequences of rapid weight loss on other organs (e.g., gall bladder, liver, etc.) and the excess skin, skin flaps and infections (e.g., yeast, staph, etc.) that may come into play or reduce one’s perception and ability of increasing activity. Use of stimulants (e.g., Adderall XR), appetite suppressants such as phentermine are other options being relied upon by some as an attempt at weight management.

Another important aspect for claims professionals to understand in the treatment of obesity is whether there are comorbid factors involved and if the patient is being treated in a multidisciplinary approach. Prior to undertaking any surgical intervention, a thorough work‑up including a mental health assessment typically occurs. Most treatment begins with conservative approaches versus leaping into invasive treatments.

Extra risks with comorbidities?

Some of the issues often experienced in obese individuals include both physical and mental health conditions. In some, isolation may lead to depression and anxiety. Treatment in these extreme cases may include simple baby steps. For example, orienting individuals to focus on getting out of the house even for noticeably short periods of time, such as going to the mailbox. For those where weight is manageable, increasing activity and healthy nutrition is often a journey begun with a multidisciplinary team: nutritionist, bariatric provider, psychologist, and even a sports medicine provider. As a claims professional, understanding who makes up the multidisciplinary team is important but more important is who is coordinating the overall care. Each of these providers may have a treatment regimen for the individual – but how it all comes together is key.

Body shape is also of importance when one thinks about managing obesity in a comorbid fashion. Understanding if a body shape is pear, oval, or round, and where the bulk of the weight is carried, has much meaning. If the weight is carried all around the waist and upper body, this may put more strain on the heart. If pear shaped, most of the weight tends to be around the hips and lower part of the body. This is suggestive of potential issues with the joints to carry the body. One of the conservative approaches on pear-shaped bodies is to ensure the feet can carry the weight. Proper footwear is important and may help to take some of the pressure off the joints. Again here, a 10% drop in overall body weight may also alleviate some of the pressure on the joints especially if one’s occupation involves prolonged periods of standing, walking, or traveling. Many having knee replacements are encouraged to try out HOKA sneakers.

Dr. Casey Kerrigan, founder of OESH shoes, spent years researching gait and the effects of footwear on the body. Pain clinicians know the obstacles faced by individuals with chronic pain and obesity. They realize in some instances how hard it is to move, that exercise may flare pain (perceived or realized), and that they may not make the best food choices. We know, however, pain that occurs with obesity is not exclusively mechanical.

Comorbid obesity and pain conditions may be related to subtle processes that start early in life, including genetics, environmental stress, and even potential trauma. Cultural and familial coping patterns, maladaptive coping and autonomic dysfunction can also influence motivation and behavior. We know depression may magnify comorbid physical symptoms and complicate treatment.

Obesity – Physical and Mental Health Comorbidities

Going hand in hand with physical inability when one is obese is proper hygiene. This is not to say obese individuals do not take care of their hygiene and skin care. Rather, they are more prone to skin and soft tissue infections (such as cellulitis, yeast infections, etc.) given skin folds, excessive limb rubbing, periodontitis etc. This in and of itself can be a deterrent to increasing activity. Some people are embarrassed to bring the topic forward. When done, however, some simple routine actions can help.

Dr. Andrews, OB/GYN, counsels his patients to use a hair dryer on low heat on skin folds to keep the excess skin dry. Showering after any activity and keeping the areas clean is helpful. If routine hygiene is not included in the treatment regimen, it should be discussed. Some situations may include medication such as fluconazole to treat the severity of the infection, while other studies9 suggest treating the adaptive immune response and Vitamin D deficiencies as therapeutic options.

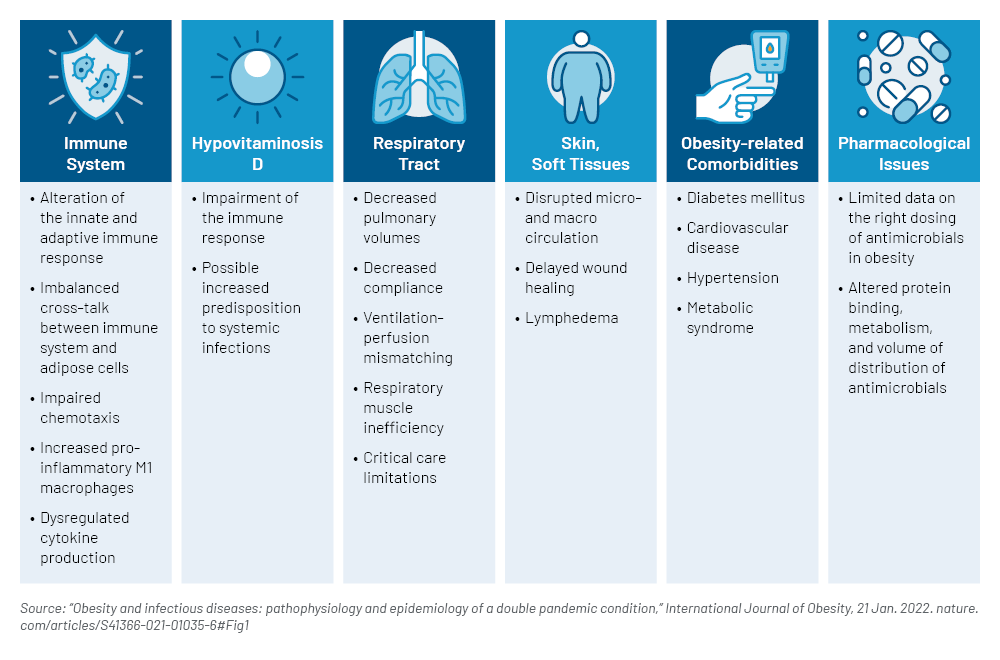

Comorbidities such as Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and cardiovascular disease can indirectly favor the onset or worsening of infections. Another common condition in obesity potentially linked to infection susceptibility is vitamin deficiency in particular Vitamin D. Vitamin D acts to suppress T‑cell driven inflammation and may prevent respiratory infections. Pulmonary physiology is significantly modified by excess weight which provides reduced lung volumes, abnormal ventilation and perfusion relationships and even respiratory muscle inefficiency.

Fatigue both physically and emotionally are not uncommon. Excess weight leads to greater fatigue of the respiratory muscles. Excess weight may also predispose some to lymphedema.

Increased Susceptibility to Infections in Obese People (Mechanisms involved)

Excess Weight Assessed as a Risk Factor for Infections

Challenges: Stigma & Bias

“Body shape is a metric that people use to judge character.”10

Individuals experiencing weight-biased stigma report more health avoidance, increased perceived judgment, discrimination, and maladaptive behavior.

- Drivers of weight gain are complex – A common misconception is that a person’s body weight is within an individual’s control and that obesity results from individual choices – and as such can be reversed easily by eating less and exercising more. This often reinforces negative stereotypes of people living with obesity (e.g., lazy, lacking willpower, etc.). Evidence shows experiencing weight stigma leads to maladaptive responses.

- Myth or Reality? – Movement is the most important thing we can do to be healthy followed by a diet of fresh, unprocessed food. Dueling influences such as the availability of inexpensive, highly processed, poor nutritional food options, and one’s ability to move may be limited due to other primary or secondary factors (e.g., injuries, joint disease, socio-economic conditions, etc.).

What’s New?

Weight loss medications, surgical approaches, treatment regimens, and research regarding the drivers and causation of obesity to mention a few. The weight loss drug market is booming with pharmaceutical innovation. Given the supply shortages and prohibitive cost of these new weight loss medications, compounding pharmacies are selling their own concoctions. This comes with tradeoffs including limited oversight/quality control measures, increased potential for misuse, limited accessibility, and unaffordability. Some of the new medications like Ozempic (marketed for diabetes) and Semaglutide (marketed for weight loss under the label Wegovy) in the U.S. range between $900‑$1200 a month out of pocket and are not typically covered by Medicare or medical carriers.

Most of the weight loss medications entering the market were initially intended and driven by diabetes care. Case in point a few years back we saw Metformin included not only in diabetic treatment regimens but also weight loss programs. The new injectables and tablets make Metformin a thing of the past with more dramatic results promised. The Atlantic reported discussion at the recent American Diabetes Association meeting in San Diego: the Age of Ozempic is already over with a new oral form of Semaglutide.11 The ability to drop 15‑20% weight in a relatively short period of time (e.g., 16 weeks) has many running to the doors of unconventional providers to gain its access including those not obese. If you can tolerate a weekly injection and its side effects (e.g., extreme fatigue, headaches, constipation, body composition changes including dysphoric/gaunt appearances, diarrhea and nausea etc.), the results can be amazing.

New data indicates the market is ripe with new options on the horizon that will only increase demand. For example, Tirzepatide and Survodutide may work better than Semaglutide and a compound Retatrutide may offer bariatric surgery-like results. It remains to be seen if the new drugs will be less expensive, convenient, or stronger and with reduce side effects.

Many of the new weight loss drugs mimic hormones (GLP‑1) that send messages to the brain triggering the sense of fullness resulting in reduced food intake but again come with some significant consequences if not monitored by a properly trained professional in bariatrics.

Not mentioned yet is the risk of dehydration which if left untreated may lead to severe complications such as seizures, brain swelling, kidney failure, shock, coma, and even death. Mild dehydration may also cause problems with blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature, fatigue, headache, skin issues and mimic cognitive dysfunction with symptoms like confusion or lacking mental clarity (e.g., sometimes referred to as brain fog). Just a 2% decrease in brain hydration may result in short-term memory loss and increase stress.12 Keeping adequately hydrated is not a cure-all but it may help those with mild to moderate cases of dehydration to recover relatively quickly with integration of fluids high in electrolytes.

Since not all complex drivers of obesity are food related, not all signing up for these new drugs achieve the promoted weight loss results. Research remains to truly address the relevance, if any, many controversial topics play in the onset and/or management of obesity such as genetics, slow metabolism, stress, emotional conditions, sleep health, gut health, poor and/or processed diets, inactivity, environmental matters (e.g., family, community, societal, socio economic status and country), and brain changes.

Commercialization and Profit

- New treatment providers are emerging, capitalizing on the weight loss medication frenzy. Enter the skin/cosmetic providers who found a way to supplement their income with injectable weight loss medication otherwise intended for diabetic conditions. The Guardian recently published an article citing online UK pharmacies are prescribing weight loss jabs to people with healthy BMI.13 The UK is not alone. Googling “Semaglutide Online” offers an array of options for the unsuspecting. Pharmacotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other interventions, such as bariatric surgery depending on the severity of the condition, all offer hope and opportunity to reduce BMI and overall weight reduction and many non-traditional treatment providers are cashing in. Again, this comes with consequences. It’s unclear if the skin care centers, medical and aesthetics businesses or online resources cashing in on the weight loss industry and new drugs provide the necessary blood work monitoring, lifestyle coaching, nutritional and appropriate treatment as a bariatrician would. Sadly, those in great need are paying the price given supply shortages. We know the new weight loss drugs come with limited access to insurance to cover costs, and these drugs are expensive. Unfortunately, some are selling them as the miracle, and those desperate to lose weight may be starting a new journey without a multidisciplinary program often seen with bariatric specialists.

- Weight Watchers’ recent announcement regarding acquiring the telehealth platform Sequence is a move into the obesity drug market by creating access to providers who can prescribe weight loss medication. (Meanwhile Jenny Craig Weight Loss Centers decided to close up shop.)

- Ozempic, Semaglutide and others soon to hit the market like Mounjaro are on distribution shortage lists and allow compounding pharmacies to sell them. Not all compounding pharmacies are the same, may not comply with FDA requirements, lack oversight and standardization on protocols. This again subjects those desperate to lose weight to potential increased risk. If not properly monitored, malnutrition and eating disorders may be unconscientious risks.

- Reality television programs like The Biggest Loser, the weight loss competition show, reported through a study following its contestants that their metabolism slowed so drastically that nearly all participants regained what they had lost. The 1000 Pound Sisters program follows two individuals, their family dynamics, relationships with food, health challenges, and treatment.

Latest News – Obesity

"Weight-loss drug Wegovy cuts stroke, heart-attack risk by 20% in new study."

- The Wall Street Journal (2023, 8 August)

"Knock-off Ozempic thrives with promise of 'huge gainz'."

- The Wall Street Journal (2023, 16 August).

List prices of GLP-1 obesity drugs far higher in the U.S. than in peer nations.

- Health System Tracker (2023, 17 August)

The cost of commercialization includes corresponding risks. If medication and treatment regimens are not closely monitored, potential risks include thyroid cancer, liver, and kidney disease to mention a few.

Some aspects of commercialization are positive. Some of the reality TV shows promote both positive messaging about the importance of one’s support system, treatment interventions and behavior modification.

Obesity Rates

The global obesity rates might surprise you – the epidemic is not isolated to any one country.

Obesity Rates by Country (2023)

The Need for Awareness

The weight loss drug market will only continue to see increased competition, with potential risks to those not treating with bariatric resources or multidisciplinary approaches to truly impact obesity. More needs to be done for the most rural and less developed communities to help increase the awareness of and access to nutrition, lifestyle modifications, and care. Increasing the awareness of varying implications and causes of obesity should be the starting point.

In the meantime, claims organizations can ensure they equip their teams with increased knowledge on this complicated and multifactorial subject. It’s important for claims professionals to stay abreast of the challenges and medical advances on the obesity front as a means to assist their clients in navigating return to function support of their claimants.

Although this article offers some insight on the complexities involved with obesity, I close with the gentle reminder that each claim is unique and should be managed on its own unique set of circumstances.

Many thanks to Rodney Voisine, MD, BS. Pharm., (board certified in Anesthesiology and Obesity medicine) for the time spent with me on this important topic.

- WHO Fact sheets, “Obesity and overweight,” 6 June 2021, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- NIH/National Library of Medicine, NCBI.nlm.nih.gov.

- NICE/National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, “Obesity: identification, assessment and management,” 8 September 2022, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189/chapter/Recommendations#assessment.

- World Health Organization

- NIH/National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4539812.

- Sharma A.M., Kushner R.F., “A proposed clinical staging system for obesity.” International Journal of Obesity. 2009;33(3):289–295. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.2, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19188927.

- Swaleh R, McGuckin T, Myroniuk TW, Manca D, Lee K, Sharma AM, Campbell-Scherer D, Yeung RO. Using the Edmonton Obesity Staging System in the real world: a feasibility study based on cross-sectional data. CMAJ Open. 2021 Dec 7;9(4):E1141-E1148. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200231. PMID: 34876416; PMCID: PMC8673483, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8673483.

- Horie NC, Serrao VT, Simon SS, et al., Cognitive effects of intentional weight loss in elderly obese individuals with mild cognitive impairment, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:1104-1112; Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training and vascular risk monitoring vs control to prevent cognitive decline in at risk elderly people: a randomized control trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2255-2263.

- International Journal of Obesity, “Obesity and infectious diseases: pathophysiology and epidemiology of a double pandemic condition,” 21 January 2022, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41366-021-01035-6.

- Connor Friedersdorf, “The Many Ripple Effects of the Weight-Loss Industry,” The Atlantic, 6 February 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/archive/2023/02/the-many-ripple-effects-of-the-weight-loss-industry/672963.

- Daniel Engber, “Goodbye, Ozempic, The Atlantic, 27 June 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2023/06/ozempic-pills-obesity-drugs-semaglutide/674541.

- Solari Mental Health, https://www.solarimentalhealth.com/behavioral-health-services-blog.

- The Guardian, “Online UK pharmacies prescribing weight loss jabs to people with health BMI,” https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/may/10/online-uk-pharmacies-prescribing-weight-loss-jabs-to-people-with-healthy-bmi-investigation.

- European Journal of Clinical Nutrition: “Competing Paradigms of Obesity Pathogenesis: Energy Balance versus Carbohydrate-insulin Models,” published 07/28/22

- The New Yorker: “Will the Ozempic Era Change How We Think About Being Fat and Being Thin?” Jia Tolentino, published 03/20/23

- The Atlantic: “The Trouble With Ozempic,” Kelli Maria Korducki, published 04/07/23

- The Atlantic: “Ozempic Is About to be Old News,” Yasmin Tayag, published 04/04/23

- The Atlantic: “In the Age of Ozempic, What’s the Point of Working Out?,” Xochitl Gonzalez, published 03/25/23

- Huffpost: “Lap-Band Gastric Weight Loss Treatment Ruined My Life,” William Horn, published 03/17/23

- The Atlantic: “The Many Ripple Effects of the Weight-Loss Industry,” Conor Friedersdorf, published 02/06/23

- The Atlantic: “The Weight-Loss Drug Revolution is a Miracle – And a Menace,” Derek Thompson, published 01/27/23

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

- Elsevier: “Obesity Stigma as a Globalizing Health Challenge”

- The Lancet: “Pervasiveness, Impact and Implications of Weight Stigma,” published 5/2022

- World Health Organization (who.int)

- International Journal of Obesity