-

Property & Casualty

Property & Casualty Overview

Property & Casualty

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Expertise

Publication

High-Low Agreements Can Prevent Large Plaintiff Verdicts

Publication

Medical Marijuana and Workers’ Compensation

Publication

Secondary Peril Events are Becoming Primary en

Publication

Risks of Underinsurance in Property and Possible Regulation

Publication

Benefits of Generative Search: Unlocking Real-Time Knowledge Access

Publication

Battered Umbrella – A Market in Urgent Need of Fixing -

Life & Health

Life & Health Overview

Life & Health

We offer a full range of reinsurance products and the expertise of our talented reinsurance team.

Publication

Thinking Differently About Genetics and Insurance

Publication

Post-Acute Care: The Need for Integration

Publication

Trend Spotting on the Accelerated Underwriting Journey

Publication

Medicare Supplement Premium Rates – Looking to the Past and Planning for the Future U.S. Industry Events

U.S. Industry Events

Publication

The Future Impacts on Mortality [Video] -

Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center Overview

Knowledge Center

Our global experts share their insights on insurance industry topics.

Trending Topics -

About Us

About Us OverviewCorporate Information

Meet Gen Re

Gen Re delivers reinsurance solutions to the Life & Health and Property & Casualty insurance industries.

- Careers Careers

The Current Inflationary Spiral – What’s Driving It? [Part 2 of 3]

February 01, 2023

Tim Fletcher,

Jonathan Rodgers, NAMIC VP – Finance (guest contributor)

Region: North America

English

This is part two of our three-part series – in collaboration with NAMIC – examining inflation and its impact on insurers.

As we moved through 2022, it became increasingly clear the inflationary pressures seen in 2020 and 2021 had settled in for an extended stay. Consumers and businesses scrambled to compensate for skyrocketing costs and inflation levels not seen since the early 1980s. Analysts and commentators warned that the “zero inflation” era seen over the previous decade had come to an end. Now, with some signs suggesting that inflationary pressures have somewhat stabilized, it’s instructive to examine what’s been driving them.

Unanticipated “Shock” Events – COVID and Ukraine

COVID’s 2020 sting left many either unable (due to governmental lockdowns or restrictions) or unwilling (because of varying individual perceptions of risk) to purchase services. Empty planes and “ghost town” central business districts painfully showed the cratering of the service economy. In contrast, consumer demand for goods soared, driven by work-from-home and the desire for personal comfort. Into the mix came the Federal Reserve, cutting its policy rate from 2.25 to zero, and a massive fiscal stimulus package from Congress and the Trump administration. By mid‑2020, real disposable income had expanded on a four-quarter basis at a mid-teens rate while real gross domestic product contracted. Never had this country given itself so much more than it had produced, in turn dislodging a long-term trend of subdued goods prices caused by globalization and technological advances.1

Through 2021 many held the view that as the pandemic subsided, inflation would prove transitory, with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell commenting that “[t]here is little reason to think” that global deflationary forces “have suddenly reversed or abated.”2

Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine obliterated that prevailing view. Energy supplies were disrupted, and commodity prices nudged upward. Economic sanctions further tangled already-stressed supply chains. The net result? Higher demand for goods with lower, and more costly, supply.3

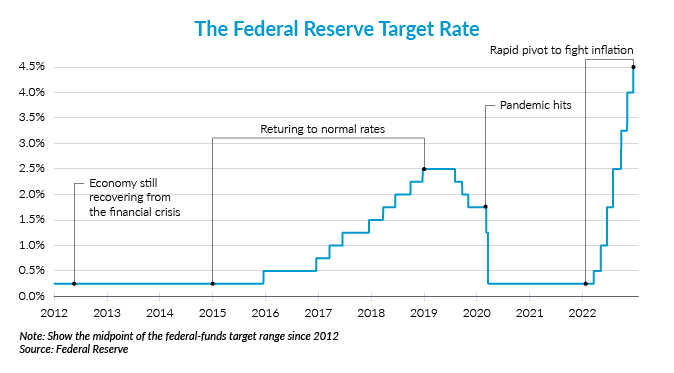

The Federal Reserve

In mid-December, the Federal Reserve approved an interest rate increase of 0.5 percentage point while signaling plans to lift rates in smaller increments through the spring as it works to combat inflation.4 The announcement followed four consecutive larger increases and raised the federal funds rate to a range between 4.25% and 4.5%, a 15‑year high.5 Considered one of the most important interest rates in the U.S. economy, the federal funds rate influences short-term interest rates for everything from home loans to credit cards.6

Analysts posit that the smaller future increase reflects the Fed’s belief that the “heavy lifting” necessary to mitigate inflation’s initial sting has taken hold, that future private-sector spending will be restrained, and that it will be able to steer the economy toward its stated dual goals, keeping inflation at 2% annually and maintaining maximum employment. However, quelling inflation carries the risk of teetering the economy toward recession. Cutting rates too soon once unemployment rises risks a repeat of the Fed’s “stop-and-go” tightening of the 1970s, which resulted in prolonged inflation coupled with high unemployment and gave rise to the dramatic Fed rate increases of the early 1980s.7

Above all these concerns is another reality: Because inflation data lags behind economic activity, by raising rates too high, the Fed may end up weakening the economy more than anticipated.8

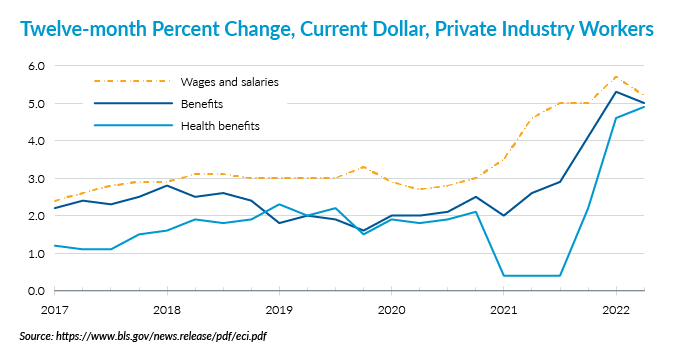

Wage Pressures

With inflation has come a concomitant increase in wages and salaries. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, compensation costs for private industry workers increased 4.1% in September 2021 and 5.2% for the 12‑month period ending in September 2022.9 The insurance industry saw an increase of 5.0% in September 2021 and 3.0% in September 2022.10

With looming uncertainty as to if and when inflationary pressures might subside, wage increases appear likely to continue for the private and public sectors. For example, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) recently adopted a recommended 8.5% increase in salary recommendations for key insurance department staff, on top of the 4.5% increase recommendation for 2021.11

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

As Published in “Financial Condition Examiners Handbook” |

3.00% |

2.00% |

1.00% |

4.50% |

*8.50% |

As Published by BLS |

2.95% |

1.53% |

0.99% |

5.37% |

8.52% |

Difference | 0.05% |

0.47% |

0.01% |

0.87% |

0.02% |

*Suggested change |

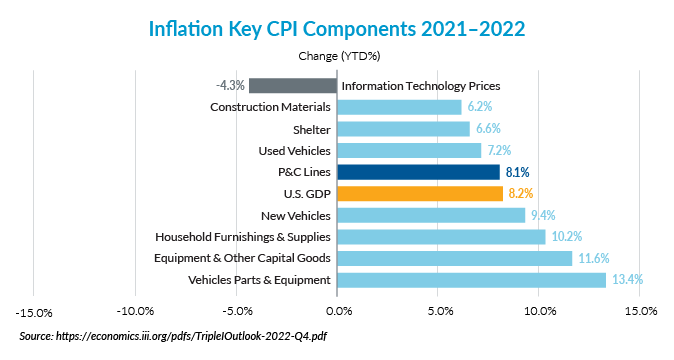

Impact on the Insurance Industry

More and more individuals and businesses are being impacted by natural catastrophes due in part to sharp increases in populations in areas prone to hurricanes and wildfires. This presents many challenges and opportunities for the insurance industry. Social inflation, too, has added increased pressure on the industry in recent years, and further adding to the industry’s woes is inflation. A recent McKinsey study estimates that in 2021, rising prices contributed roughly an additional $30 billion in loss costs beyond historical loss trends.12

There’s some thought that increased loss costs may be the norm going forward, with the Insurance Information Institute (III) suggesting that while auto prices and construction materials have come down from pandemic highs, and supply chains have stabilized, labor costs remain elevated. Moreover, the III warns that we could see a return of stagflation, characterized by low or negative growth coupled with high inflation, in turn depreciating asset values without any growth upside.13

What does stagflation mean for the insurance industry? It potentially can impact both sides of the balance sheet and put pressure on insurer profitability. Product lines like Homeowners and Auto would be impacted by rising prices in construction and car parts, while asset values and capital levels would also be negatively impacted due to potentially lower equity markets and widening credit spreads.

The Future

There exist divergent views as to what the economic future might hold. The most optimistic view has it that food, energy, and commodity prices stabilize, and that inflation recedes in 2023.14 Another is that the lasting effects from COVID-inspired lockdowns continue to hamper economic well-being, which when combined with a possibly protracted Eastern European conflict fuels ongoing inflation. This scenario may cause the Fed to hike rates to a degree that could risk triggering a significant economic contraction, especially if the rate increases are done too swiftly.15 Still another – and less likely – view is that pandemic- and conflict-related disruptions drive global energy and commodity prices to longer-term elevated inflation beyond the Fed’s control, in the process ushering in an era of 1970s-style stagflation.16

Forecasts of this type are uncertain, especially in the context of the current unique global economic conditions and related policy responses, and unforeseen events often carry outsized impacts. Regardless, the future brings with it uncertainty and myriad challenges. And, if history once again proves to be an accurate indicator, the insurance industry – with its risk management and forward-looking mindset – will continue to navigate to support and protect policyholders, meeting the challenges ahead.

Endnotes

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/inflation-2022-what-happens-next-11670867683

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/powell-says-fed-could-start-scaling-back-stimulus-this-year-11630072789?mod=article_inline

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/inflation-2022-what-happens-next-11670867683

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/fed-raises-rate-by-0-5-percentage-point-signals-more-increases-likely-11671044561?mod=economy_more_pos23

- Ibid.

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/federalfundsrate.asp

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/powell-federal-reserve-interest-rates-inflation-11670859520

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/for-the-fed-easing-too-soon-risks-repeat-of-stop-and-go-1970s-11657454403

- https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/eci.pdf

- Ibid.

- https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/call_materials/Risk-FocusedSurveillanceWG_11-1_Materials.pdf

- https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/financial%20services/our%20insights/ countering%20inflation%20how%20p%20and%20c%20insurers%20can%20build%20resilience/ countering-inflation-how-us-p-and-c-insurers-can-build-resilience.pdf?shouldIndex=false

- https://economics.iii.org/pdfs/TripleIOutlook-2022-Q4.pdf

- https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/financial%20services/our%20insights/ countering%20inflation%20how%20p%20and%20c%20insurers%20can%20build%20resilience/ countering-inflation-how-us-p-and-c-insurers-can-build-resilience.pdf?shouldIndex=false

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Jonathan Rodgers serves NAMIC as the Director of Financial and Tax Policy. His responsibilities include representing member-company interests in the areas of solvency regulation, state and federal tax issues, and international policy affairs. He covers developments at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors for any new standards or policy changes that impact U.S. property/casualty insurers.

Jonathan Rodgers serves NAMIC as the Director of Financial and Tax Policy. His responsibilities include representing member-company interests in the areas of solvency regulation, state and federal tax issues, and international policy affairs. He covers developments at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors for any new standards or policy changes that impact U.S. property/casualty insurers.